Intelligence

People Think They're Better Than Average, but How Much Better?

The Better-Than-Average Effect is big, but it depends on how (not who) you ask.

Posted January 23, 2020 Reviewed by Matt Huston

Psychology Today readers will likely be familiar with the popular research finding that most people believe they are above average on desirable traits like intelligence, friendliness, and sincerity. But just how far above average do people tend to place themselves? A recent, large-scale meta-analysis finds that the answer depends on how you ask (Zell, Strickhouser, Sedikides, & Alicke, 2020).

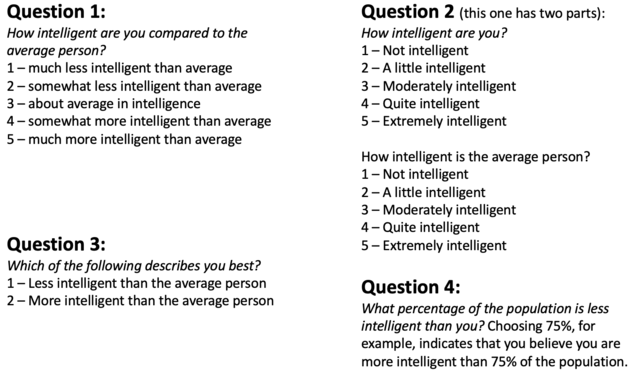

In the image below, consider a few different ways of asking someone if they think they are smarter than average. After all, intelligence is viewed as one of the most desirable traits a person can have (Alicke, 1985).

Before I reveal the results, can you guess which of the four questions above is most likely to make people claim that they are smarter than average? Which is the least likely? Which of these questions would be most likely to get you to claim superiority over others?

Ordered from the largest effect to the smallest, the answer is:

- Question 3

- Question 1

- Question 2

- Question 4

Researchers who study the Better-Than-Average Effect (BTAE) have been asking people variations of these questions for decades. Choosing which question to use may be theoretically informed or important. For example, perhaps it is important to have a measure that ranges from 0-100, making Question 4 the obvious solution. My guess, however, is that the decision of which question to use is made near-arbitrarily. After all, researchers who use any of these questions want to know the same basic thing: Do people think they are more intelligent than average?

Zell et al.’s meta-analysis examined the results of 124 published papers that asked a combined total of over 950,000 research participants some version of one of the four questions listed above. There are many other ways to solicit better-than-average beliefs, of course, but these four are historically the most popular.

What did Zell et al.’s research find? First, the meta-analytic results confirmed that yes, people do tend to believe they are above average on positive traits and abilities. Just how far above average? Their effect size estimate was d = 0.78. This falls somewhere in between two more readily interpretable effect sizes: the finding that, on average, women own more shoes than men (d = 1.07) and the finding that, on average, men weigh more than women (d = 0.59) (Simmons, Nelson, and Simonsohn et al., 2013).

Knowing that the average size of the Better-Than-Average Effect is d = 0.78, does how you ask the question boost or shrink the effect? Question 3, which forces a choice between “above average” and “below average,” had the largest effect, d = 1.0. Question 1, which measures a direct comparison in a single question, was close behind at d = 0.91. Question 2 requires two answers: one rating of yourself and one rating of the average person. This question produces a substantially smaller effect, d = 0.70. Finally, the question that requires a percentile estimate (Question 4), had the smallest effect, d = 0.62, though this effect can still be considered medium or large by common social scientific heuristics.

What else did we learn about the Better-Than-Average Effect from this massive meta-analysis of studies? A few additional interesting takeaways are listed below.

- The Better-Than-Average Effect tended to be larger for traits than for specific abilities. This may be unsurprising, as traits are harder to measure and harder to prove. In other words, they may be easier to fudge.

- The meta-analysis revealed no significant effects of cultural background on the magnitude of the BTAE. This is an interesting contribution to the ongoing debate over whether overconfidence and self-enhancement truly exist in both geographically western and eastern cultures.

- There was also no effect of gender on the overall effect size of the BTAE. This may push back against many people’s intuitions and similarly against some research that finds men tend to be more overconfident than women (Barber & Odean, 2001; Heck, Chabris, & Simons, 2018).

- Finally, there were robust positive correlations between the BTAE and two measures of well-being, including self-esteem (r = .34), and reported life satisfaction (r = .33). For better or for worse, this suggests that feeling good about yourself is related to feeling superior to others.

What does all of this mean in practical terms? There are two clear takeaways. First, across decades of research and close to one million research participants, the evidence for the Better-Than-Average Effect is nearly undeniable. During a scientific moment where popular effects are increasingly challenged both by new theories and through direct replication attempts, the finding that people see themselves as above average appears to be robust, pervasive, and by most accounts, large.

Second, and perhaps more interestingly, it means that what we believe about ourselves often depends on how these beliefs are solicited. This knowledge can be useful. Asking people to give a specific percentile estimate of their own ability (as in Question 4), for example, may diminish people’s sense of self-superiority relative to the other approaches. Conversely, simply asking people whether they believe they are better than average (as in Question 3) may be able to boost confident, self-enhancing thinking. A shrewd but perhaps disingenuous leader might pick and choose among questions like these in order to argue that her employees, students, or followers are more humble, or more hubristic, than most. The fact that the Better-Than-Average Effect depends so strongly on how these beliefs are solicited may even suggest that the phenomenon is more of a state than a trait. If this is the case, then self-positivity may be less of a stable trait—and more of a response to idiosyncrasies of the stimulus—than many social and personality psychologists would like to admit.

Facebook image: Maksim Ladouski/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: mentatdgt/Shutterstock

References

Alicke, M. D. (1985). Global self-evaluation as determined by the desirability and controllability of trait adjectives. Journal of personality and social psychology, 49(6), 1621.

Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2001). Boys will be boys: Gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment. The quarterly journal of economics, 116(1), 261-292.

Heck, P. R., Simons, D. J., & Chabris, C. F. (2018). 65% of Americans believe they are above average in intelligence: Results of two nationally representative surveys. PloS one, 13(7), e0200103.

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2013, January). Life after p-hacking. In Meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, New Orleans, LA (pp. 17-19).

Zell, E., Strickhouser, J. E., Sedikides, C., & Alicke, M. D. (2020). The better-than-average effect in comparative self-evaluation: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(2), 118.